A Wellbeing Improver’s experiment

What’s on your mind today?

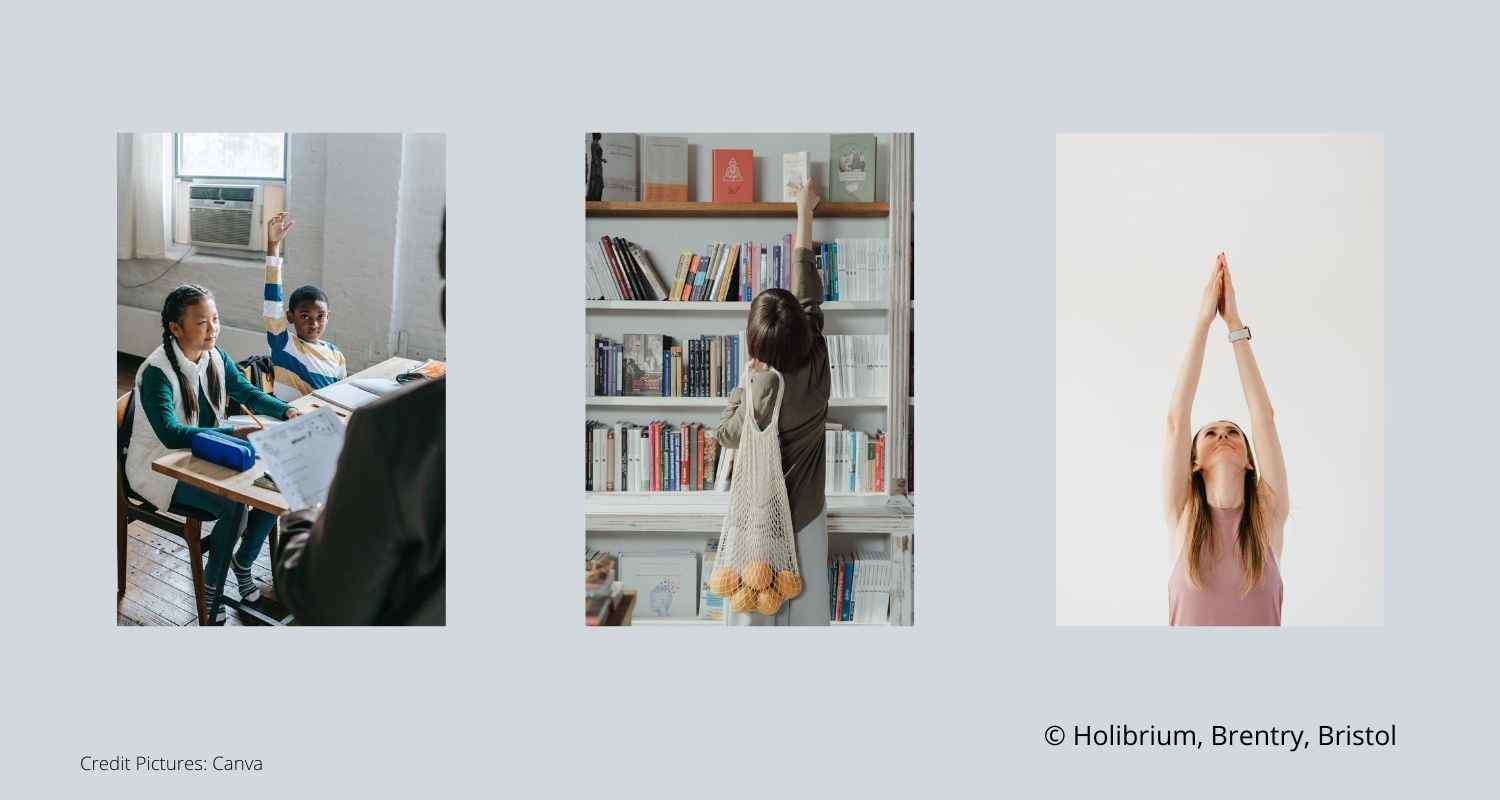

I would like to raise my arm, past my shoulder.

Why are you interested in this?

I find this movement painful and I am experiencing

a pulling in my shoulder

(gleno-humeral joint).

Wellbeing Improver does not currently have any injury. She, however, mentioned that a few years back she had a ski injury and did something to her tendons; she also had a mastectomy on the left side, which meant that for a while she was doing more with her right arm.

A performance baseline

We started the session with Wellbeing Improver showing me her activity.

When she raised her left hand, she could not raise it very high without some discomfort.

There was also some movement at the hip joint together with the raising of the arm.

Our interaction together

We started with the head/neck relationship which brought about more mobility in the head/neck relationship.

We then did some work with the arm.

We also talked about a few ideas: we talked about the different joints in the arms, we talked about where the arms connect to the body, we talked about the fact that the hips are not the gleno-humeral joints and that they do not have a lot to do with the activity of raising one’s arm.

What does this mean in terms of movement?

Here is the outcome of our work together

Wellbeing Improver noticed, after our work and verbal interactions, that, when raising her arm, the movement was neater and required less energy. The movement felt different, and she did not need to accompany it with this big movement from the hips.

She came to discover that she was bringing tension into her right shoulder at the thought of raising her arm and reaching

upwards. She acknowledged she did not need to do that, even though in the past she thought there had been a use for bringing

this muscular contraction and tension in her right shoulder. As she put it, this tensioning of the shoulder was an

archaic

movement behaviour that did not really have its place in the current and present circumstances.

Such a realisation and acknowledgment brought about a different relationship of the arm with the body (trunk). When she performed

the activity of raising her arm once more, Wellbeing Improver

liked the way [she] moved, liked the fact that she can change how she moves

.

It does not have to be painful and a lot of effort

.

A positive experience

Wellbeing Improver went through the process of raising her arm. She found out that she could perform the activity of raising her arm

more easily without pain. She furthermore realised that her elbow and wrist had moved

: the movement

felt easy and very smooth

,

with the different parts of the arms just following one bit after another

.

Wellbeing Improver finds her movement sessions (Alexander Technique) life changing as she is able to move differently. She is gradually

improving which is a better outlook to “oh, I’m getting older, it is difficult to move”

.

She stopped doing what she thought she had to do in the past and was still doing in the present. As a result, the interference stopped, and she is now able to raise her arm easily.

Transferability

These new ideas are not bound to this specific session. They can be used in many everyday activities such as reaching up into a cupboard, raising our hands, fitness exercises, etc.

This may be of interest to you

![There is a way out if only [we] take it... by Kurz and Prestera Quote by Kurz and Prestera](images/quote_30_04_22_there_is_a_way_out_1500C.jpg)