I have been working with a thirteen-year-old complaining about back issues. We had a few movement sessions in which we applied F.M. Alexander’s ideas and principles

Text neck

As always, during our interaction, we chat, we

exchange ideas, and we focus on the general before going to the specifics.

So, one of the first things we did was work with the head/neck relationship with

the body in movement as it is the key to freedom and ease of

motion

(Weed).

That relationship was very rigid and very stiff. As many teenagers and older people, our Wellbeing Improver tends to lead her chin towards her screen; she has what is called at times a ‘text neck’ or a ‘tech neck’. Rather than moving from her hip joints which would give her a greater range of motion, she moves from her neck, which translates into her neck being forward relative to her body. As she does this nth times during her day, she finds herself in chronic pain in her back.

During our session, experimenting moving from the hip joint, rather than from the neck to look at her screen when she wants to get closer to it, Wellbeing Improver managed to stop her usual movement behaviour.

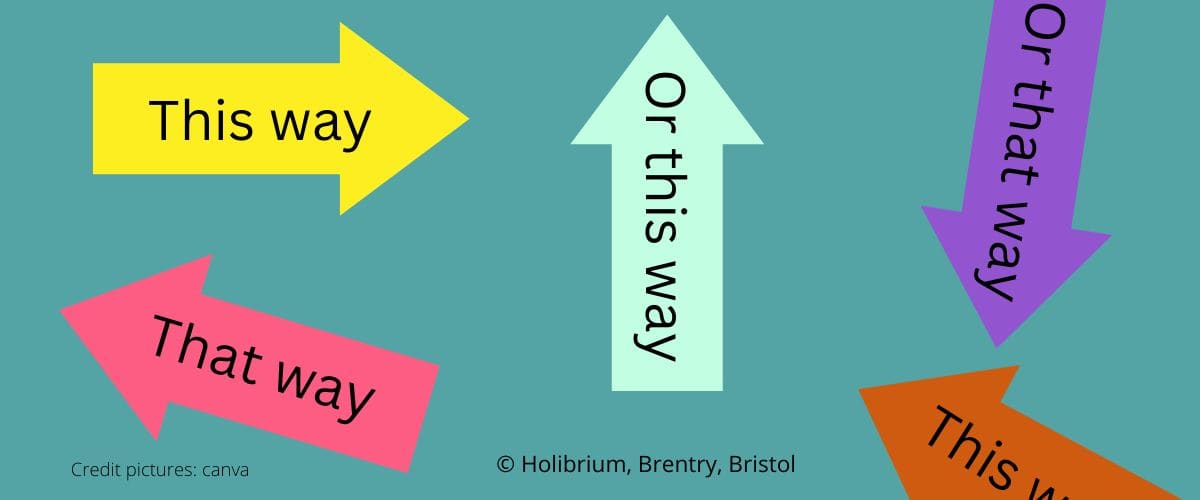

The payoff of a different pathway

As a result of that change, she had more movement in her head/neck relationship and was moving her head and her body to look at the screen in a different manner. That different pathway brought about more mobility and eased the pain she was experiencing in her back.

I have less bones!

What she found out for herself was that she had “less bones in her neck”! Bones have the ability to move in relation to one another and those in the neck form the cervical spine. She was not, however, talking of those bones. She was referring to the ‘bones’ on the side of her neck. You would be right to ask: which bones on the side of the neck?

A bit of background information

Bones, muscles, and connective tissues (fascia) are usually defined as distinct entities. However, while the embryo develops, bones, muscles and connective tissues all originates from the cells of the mesenchyme. Bones, muscles and connective tissues are specialisation of the same tissue and can then be said to be on a spectrum from + soft to + hard. If so, one can say that bones are “mineralized condensation of fascia” (Scarr 2018). Levin also says that bones “are soft-matter gels, that may have either a rigid or compliant phase”.

If it can be so of bones, there is no reason why it cannot also be so for muscles: they can have a rigid and a compliant phase.

What was happening?

From what our teenage Wellbeing Improver said one can infer that the muscles on the side of her neck were heading more towards a rigid phase, which is not usually their permanent biological phase. By being constantly more towards the rigid phase, the side neck muscles were also modifying the geometry of the structures of the neck.

It is not that she had less bones in her neck, it is that the side muscles stopped being on a rigid phase, a rigidity Wellbeing Improver associates with ‘being a bone’.

Exploring new ideas and having a different understanding brought about positive changes. Judging by Wellbeing Improver’s smile, the ‘loss of a few bones’ was not such a bad thing!

You might also be interested in: